Dedication: To the Passenger Pigeon

Ectopistes migratorius

(amimi—Lenape, omiimii—Ojibwe, mimia—Kaskaskia Illinios,

ori’te—Mohawk, putchee nashoba—Choctaw, for lost dove)

In whose nomadic etymology is its future

passing by,[1]

Pleistocene – Anthropocene

100,000 years Before Present – 1914 Common Era.[2]

It flew at a speed of 100 km/h.

Its song may have sounded “like the creaking of a tree.”[3]

![]()

![]()

Land + Sky Acknowledgment

pussekesèsuck (Narr.);

pissuksemesog very small birds [5]

![]()

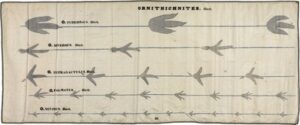

[1] From the entry for “Passenger Pigeon” on Wikipedia: “The genus name, Ectopistes, translates as ‘moving about’ or ‘wandering’, while the specific name, migratorius, indicates its migratory habits. The full binomial can thus be translated as ‘migratory wanderer’. The English common name ‘passenger pigeon’ derives from the French word passager, which means ‘to pass by’ in a fleeting manner” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Passenger_pigeon).

[2] The Passenger Pigeon was a member of the pigeon and dove family, Columbidae. Fossil records show that it inhabited the eastern deciduous forests of present-day Massachusetts from the Pleistocene Era more than 100,000 years ago until the very edge of the Anthropocene when it was declared extinct in the wild in 1901 and in captivity in 1914: “A slow decline between about 1800 and 1870 was followed by a rapid decline between 1870 and 1890. The last confirmed wild bird is thought to have been shot in 1901. The last captive birds were divided in three groups around the turn of the 20th century, some of which were photographed alive. Martha, thought to be the last passenger pigeon, died on September 1, 1914, at the Cincinnati Zoo. The eradication of the species is a notable example of anthropogenic extinction” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Passenger_pigeon). The earliest written record of its presence in Massachusetts appears in 1630-31: English settlers noted that so “many thousands” appeared in the skies that they “obscured the light” and “covered” the horizon. The last Massachusetts record for the Passenger Pigeon was entered in 1903 by an observer noting just 25 birds near Crystal Lake (see A. W. Schorger @ http://passengerpigeon.org/states/Schorger-MA.pdf; The Passenger Pigeon: Its Natural History and Extinction. Madison: U of Wisconsin P, 1955.) Deforestation and pervasive hunting played principal roles in its extinction.

[3] Although it once migrated in flocks of 3-5 billion birds, causing “a torrent” and “a noise like thunder” (John James Audubon,Ornithological Biography 1831, describing his experience of an 1813 migration) not a single recording of its wingbeats, calls, or songs exists. For this description of its song, see A. W. Schorger’s 1855 April record, Middlesex County, Massachusetts @http://passengerpigeon.org/states/Schorger-MA.pdf; The Passenger Pigeon: Its Natural History and Extinction. Madison: U of Wisconsin P, 1955). In the birdscapes for April-September, the months in which the Passenger Pigeon was present in Massachusetts, we have included sounds made by one of its closest genetic relatives, the New World Ruddy Pigeon (Patagioenas subvinacea).

[4] In forming this acknowledgement, we are especially indebted to all those who helped to compose Map by Native Land Digital, a map of Indigenous Nations of Massachusetts, https://native-land.ca.

[5] The New England Algonquian definitions of “bird” are provided Frank Waabu O’Brien (Aquidneck Indian Council); see http://www.bigorrin.org/waabu4.htm.